By Emily Nathan

El Anatsui, contemporary art’s master of recycled scrap metal, never wears gloves. A habit of bare hands can be worrisome for some artists, but for Mr. Anatsui, it’s downright dangerous: his works may resemble glittering tapestries, but really they’re all barbs and sharp edges, a rough network of flattened and hammered metal parts, hinged with copper wires into massive sheets of rippling armor.

“You develop a kind of relationship with the materials that you know how to touch them and they won’t cut you,” Anatsui told us last week, fondling a net of twisted metal rings installed at Jack Shainman Gallery for his current exhibition, “Trains of Thought.” The artist is perhaps best known here for his Brooklyn Museum retrospective of 2013.

“You need to feel what you are doing—if you put on gloves you can’t feel,” he went on. “My assistants and me, we work with bare hands.”

Born in Ghana in 1944, the artist moved to Nigeria after graduating from the University of Science and Technology and quickly surged to the forefront of the Nsukka group, which is known for integrating the traditional practice of uli design into contemporary art. Anatsui’s signature compositions embody his ongoing exploration of non-fixed form, which he began in the mid 1990s with recycled wood panels arranged in modifiable sequences.

“Their flexibility is one of the concepts that I have worked with—the idea of flexibility and freedom, to first of all relate to each other in various ways, but also to shape themselves in ways that are not fixed,” the artist said.

So, too, with his abstract metal works. They arrive at a gallery folded and piled in a small box. Where and how they should be displayed—whether hung flat on the wall, bent, folded, tilted, or left free-standing on the floor—is not specified, left instead to the discretion of art handlers.

“The first piece I did was actually hanging in the middle of the studio like a curtain,” Anatsui recalled. “But I think that galleries tend not to prioritize the space that you can move around in. They all deal in walls, so I’ve noticed that works I originally meant to be things that you move around end up hung on the wall all the time.”

In the late 1990s, Anatsui moved to his scrap metals works, inspired by the different types of metallic trash that litters the Nigerian landscape. He was especially attracted to aluminum liquor bottle caps, which he took to be tokens of the brutal history of cross-cultural exchange.

“I asked myself, how did bottle caps come along, because they’re not a thing indigenous to West Africa,” the artist explained. “So it didn’t take long to find out that, OK, these things were brought in by Europe for trade by barter, and as time went on they exchanged them for so many things, including humans. Slaves were bought with drink and brought here, and they would produce sugar cane used in more drinks to go to Europe and ship some back to Africa, to exchange for more. No matter how you look at it, these caps are a strong link factor between continents and peoples.”

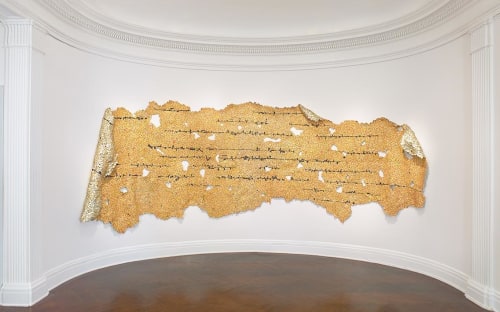

Site-specificity has not traditionally been part of Anatsui’s project—until now. Opening October 28 at Mnuchin Gallery on the Upper East Side, a second exhibition organized by Sukanya Rajaratnam debuts a brand-new series the artist made for the gallery’s historic, three-story townhouse.

The series, “Metas,” marks a departure from the color-saturated bottle cap works he has been producing in recent years. Instead, they are primarily monochromatic, mostly featuring chalky expanses of white, silver, gold and gray, turning in the light like the inside of an abalone shell.

Meta II courses with serpentine waves that evoke a Futurist deconstruction of human form and upstairs, the sculptural Womb of Time is hung from the ceiling and hovers just above the floor, like a seething nest shot through with holes. There’s no bottle caps to hint at the dark history of transatlantic trade winds, but the evocation of his home continent is there.

“I think the process too is symbolic—the process of linking the parts together, and linking them in a way which is not fixed, in a way that the relationship can change,” Anatsui reflected. “Like you can have a big piece, and when you fold it, things that have fallen apart can come together and fall apart again.